Friday, April 8

Lies and details

Thursday, March 3

Lessons

In this unconventional American Western, How Much of These Hills Is Gold, a Chinese-American family pursues a hardscrabble life, prospecting for gold and working other mines with two goals. Ba, the father, wants to buy his own plot of land, and the mother longs to return to China. Set in the mid-1800s, the family confronts slurs and discrimination while the two daughters – Lucy and Sam, ages 12 and 11 – endure a mixture of abuse and tough love at home. It's easy to imagine members of this family questioning, “can you love a person and hate them all at once?”

Both girls are smart, adapting to new settings, as the family moves in search of work and a sense of home. Lucy openly yearns for a formal education, much like Sofi in Fear of Beauty, but poverty, discrimination and her father’s general mistrust prevent her from consistently attending classes. Sam, with another set of desires, nurtures the ability to keep secrets.

The story begins after their father’s death in 1862 and the girls’ flight from a mining town, and the book leaps from past to present and back, with the story of the journey, separation, reunion and a heap of painful memories: their father’s upbringing and parents’ meeting, the death of a baby brother, their mother’s disappearance, the quest for work, comradery, and respect.

The parents make no secret of their longtime preference for a son, and Sam takes to cutting her hair, dressing in boy’s clothes and accompanying her father to the mines for work, all the while regarding her body as “a temporary inconvenience.” Lucy struggles to understand Sam who wants to be a cowboy, an adventurer, an outlaw and concludes that her sister is “Young enough to think desire alone shapes the world.”

Lucy gathers intently observes and listens to others – including her parents and strives to please anyone who might teach her. She discovers lessons in agreement, politeness, trickery, shame and “imagining herself better” along with the disappointing stream of “Lessons in how other people live” and “Lessons in wanting what she can’t have.”

Often, when trying to please others, when not moving through the wilderness, she loses her identity and values.

As a child, Lucy resists the notion the family might return to China, insisting she does not want to live with other Chinese, blurting out a common ethnic slur herself. Her father, in one of his gentler moods, whispers the Chinese word for Chinese people, and the two sisters “let the name for themselves drop down the cracks in their sleep, with a child’s trust that there is always more the next day: more love, more words, more time, more places to go….”

One of the most haunting parts of the book is the father’s background story, relayed after his death by the wind sweeping over the land. The orphan, raised by Natives, former slaves and others ostracized by society did not grow up with people who looked like him. “But that’s not an excuse, and don’t you use it," he admonishes Lucy. "If I had a ba, then he was the sun that warmed me most days and beat me sweaty-sore on others; if I had a ma, then she was the grass that held me when I lay down and slept. I grew up in these hills and they raised me….”

The father cherished wildness, and Lucy wondered if that was the “sense that they might disappear into the land – a claiming of their bodies like invisibility, or forgiveness?”

Other lessons are brutal and erratic as the father teaches the mother English, the mother teaches the father Chinese, and both parents guide their girls on how to be tough and endure adversity. The isolated, beautiful, and crafty mother urges her daughter to find choices: “’[B]eauty’s the kind of weapon that doesn’t last so long as others. If you choose to use it – mei cuo, there’s no shame. But you’re lucky. You have this, too.’ She raps Lucy’s head.”

The alcoholic father’s angry cruelty forges a connection between two young women with many differences. Lucy also absorbs lessons on injustice, loyalty, gratitude as well as the land's harsh beauty. “I looked for a fortune and thought it slipped between my fingers, but it occurs to me I did make something of this land after all – I made you and Sam…. I taught you to be strong. I taught you to be hard. I taught you to survive…. I only wish I’d stayed and taught you more. You’ll only have to make do with bits, as you have all your life.”

Regardless of hate, love and other emotions in between, the father repeatedly drills the girls on one key lesson. Family comes first. Ting wo. Of course, such fierce loyalty means freeing other family members freedom to go their own way.

Tuesday, March 1

Neighbors at war

Russia's president, rattled by NATO and nostalgic for the Soviet Union and Cold War, invaded Ukraine after the latter's leadership rejected a pledge to not join NATO. Russia has also threatened others. “President Vladimir Putin has demanded NATO withdraw all outside forces from the region and commit to Sweden and Finland never being allowed to join,” reports Edward Lucas for Foreign Policy.

Putin's use of brute force in Ukraine provides new incentive for Finland, Sweden and Ukraine to pursue NATO membership.

NATO leaders met on February 25, calling on Russia to stop the “senseless war” – and to “immediately cease its assault, withdraw all its forces from Ukraine, and turn back to the path of dialogue and turn away from aggression.”

NATO’s 30 allies contribute to the budget on an agreed cost-share formula based on gross national income – “This is the principle of common funding, and demonstrates burden-sharing in action.”

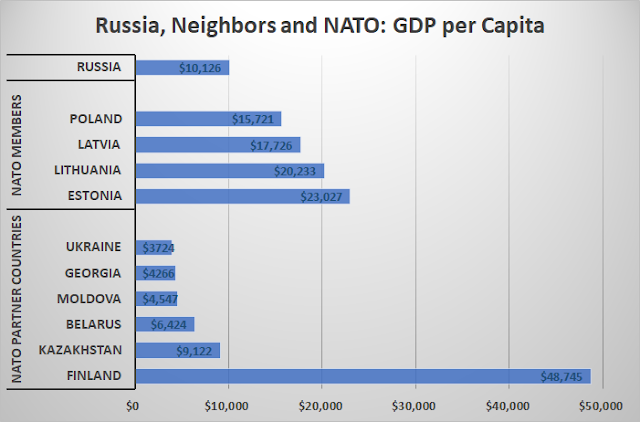

The US State Department describes US cooperation with NATO’s three Baltic State members – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The countries bordering Russia have shouldered the security responsibility, reports Lucas. “The Baltic states and Poland play their part too: Their defense budgets exceed the minimum 2 percent of GDP mandated by NATO. These funds are spent wisely, including on modern weaponry that could at least slow, and thus help deter, a Russian attack.”

NATO is supporting Ukraine against Russia’s aggression: “Thousands of anti-tank weapons, hundreds of air-defence missiles and thousands of small arms and ammunition stocks are being sent to Ukraine. Allies are also providing millions of euros worth of financial assistance and humanitarian aid, including medical supplies to help Ukrainian forces.”

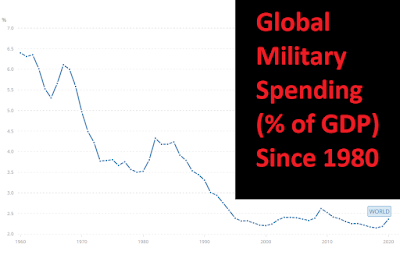

Global military spending as a percentage of GDP has been in decline since the end of the Cold War, but Russia's current leadership is intent on reversing that trend.

So far, the Ukraine military, aided by citizens under siege are slowing the Russian invasion. NATO members – along with many other countries – are imposing harsh economic sanctions on Russia that could plunge the country into a depression as long as President Vladimr Putin is in charge.

Data on military spending for Russia and selected neighbors from the World Bank.

Monday, February 28

Neighbors

Data on GDP per capita is from the World Bank.

Thursday, February 17

Inequality

The Glass Kingdom, creepy and suspenseful from the start transforms to simple horror by the end, masterfully detailing the resentments that emerge over inequality and the ways that individuals justify stealing from others: “It was a war between herself and the moneyed classes, and in that war all ruses were legitimate, all feints justified,” concludes Sarah soon after creating and selling a set of forgeries, presented as correspondence from her most recent employer, a famous author. Committing a crime eliminates social protections, and when encountering trouble later, Sarah cannot turn to authorities: “It was too late, in any case, to become an upright citizen and call the police.”

A reader

must suspend belief about the plot and numerous character decisions. Why would

the author retain her own handwritten letters to celebrities like Angela Davis

or Diana Vreeland? Why would collectors sell them to the author and not to the other

collectors seeking them and paying a premium price? Wouldn’t the collectors have

direct dealings? And Sarah’s transport of a couple hundred thousand by air, crossing

international borders, would surely be much riskier with more challenges than

described.

Then again,

people are odd, sometimes extraordinarily lucky or unlucky as the case may be. And

loneliness – so familiar during the Covid pandemic – compounds the poor

decision-making displayed throughout the novel: “The burden of that solitude

had begun to crush her hour by hour.” Sarah fails to recognize the assuming manipulations

of a new friend Mali who requires assistance in covering up another crime, not posing questions or objections after Mali suggests: “Let’s do it my way, OK?

I’m sorry to get you involved, though,” quickly adding, “We’d both like that, no?” Finally, why would a young woman not quickly abandon a hotel losing

guests, let alone a city with increasing civil unrest?

The dark and

moody novel powerfully demonstrates how inequality makes trust or mutual respect

impossible. Characters are divided not only by wealth and skill, but ethnicity

and religion. A hotel maid concludes that the farangs, referring to foreigners, are “animals in their hearts, untouched by the grace

of Lord Buddha” – and they exist in a “prison of their own making, and she

entered that prison only to make a living. For in the end there was no other

reason to enter it at all.”

The book conveys that life is unfair at every level. Highly visible, cruel inequality ensures that sinister unfairness and corruption never end.

Wednesday, February 16

Memories of love

The Parted Earth is a family saga that begins with the 1947 Partition of India. A teenager, Deepa, observing and worrying how New Delhi and neighborly relations can change violently in a short period of time, recalls a comment from her mother: “People are inherently good… they’re just not inherently good all of the time.” The comment ominously foreshadows the ethnic hatred and violence of the Partition, turning neighbors against neighbors and even some parents against children, as noted by Stanford’s Partition Archive:

“Up to two million people lost their lives in the most horrific of manners. The darkened landscape bore silent witness to trains laden with the dead, decapitated bodies, limbs strewn along the sides of roads, and wanton rape and pillaging. There was nothing that could have prepared the approximately 14 million refugees for this nightmare. The 1947 Partition of the Indian subcontinent into the independent nations of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan was accompanied by one of the largest mass migrations in human history and violence on a scale that had seldom been seen before.”

The book begins sweetly, taking on the tone of a young adult novel while describing the happy life of Deepa, the only child of two progressive physicians. But violence and chaos mark the summer of 1947 with India on “the verge of a war with itself.” The brutality and separations haunt survivors long afterwards, lingering for generations. For those who witnessed the atrocities, “Distance and time were inconsequential.” Collective grief ensures loneliness, trust is fragile, and parents struggle to explain events to their children. Withholding information about a child’s father, conceived during the chaos, is cruel. Learning horrific truths about a parent’s role in atrocities is perhaps even worse.

Deepa bears a son, Vijay, who searches for the father he never met and answers about his mother’s resentment. A search in India and Pakistan separates him from his daughter, Shanti, who is 10 and raised in the United States.

Every character, during the days of Partition and long afterward, is left feeling as if he or she could have done more – displayed more grace, more compassion, more patience.

Unlikely friendships that cross generations and cultures bring comfort, new perspectives and even rescue. For Vijay, it’s Miss Trudy – his mother’s friend who cares for him and treats him as her own. His mother was stern, ensuring completion of homework, assigning extra math problems to do and books to read, providing shelter and food. Yet “Miss Trudy taught him how to make dough rise for bread, how to sew on a button, how to draw a dragon, kick a football…. She tended to his skinned knees, comforted him when his classmates called him a half-caste bastard. Miss Trudy let him be weak, so that when his mother picked him up in the evenings, he could pretend to be strong.”

Deepa is furious after Miss Trudy poses the boy's questions about Vijay’s father. More than anything, Deepa feels “betrayal… sudden understanding about the special closeness her son shared with his babysitter, instead of his own mother.”

Years later, Shanti, wonders why Vijay, her father, was so distant, spending so much time in India. In her forties, she forms and embraces a friendship with an elderly widow next door, whose husband committed suicide, and the two women share details from their pasts.

Sharing stories and close listening pays dividends as Shanti finds the widow’s husband on a website that documents Partition experiences, and the widow locates the sister of Vijay’s father, Shanti’s grandfather, in Pakistan.

Planning for Partition and the aftermath with mass migration, surging resentment and violence, spanned a few months, but the rebirth, renewal, and forgiveness required years.

Shanti spent only a few days at a time with her father, but is grateful to have known his love. “She didn’t have it for long enough. But now, in her forties, she felt it stronger than ever. She would hold on tight to it and never let it go.” Love, however brief, is embedded in memories, providing strength to trust and care for others even while handling loss.

Saturday, January 29

The purpose of children

Scarlett Chen, impregnated by her employer, is sent to a secret home in California, with the goal of obtaining US citizenship for the infant. The employer, already married with three grown children, is possessive, "acting as if he had a right to her every thought, to her every move." Perfume Bay is more prison than resort, and Scarlett is furious when the home's manager, Mama Fang, hands over payment and expects her to give up any claim to the child. Mama Fang had hardened herself to the cruelties of such an unscrupulous business, vowing to watch out only for herself. “She did not know then that this vow would harden her. If you only looked out for cheats and con artists, you only found cheats and con artists. You became one yourself.”

Scarlett refuses to comply. Raised by an angry, controlling woman whos enforced strict one-child limits in their poor village, she resents inequality, being told what to do. And so Scarlett flees Perfume Bay. "America called to her: the land of cars, of fast highways that opened up the country that she'd always wanted to explore, the country where she could make a life for her daughter." She soon discovers that the corruption and inequality of factory work in China are not so different from the tough scrabble in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Compounding her stress – a soon-to-expire tourist visa means that she must dodge immigration authorities as well as the detectives dispatched by her lover and his friend to hunt her down.

Vanessa Hua analyzes the role of children and families, and the struggle for immigrants to the US, where “even the most prosperous had to endure snubs, slurs, and worse.” Families become insular and children become the means for pursuing a better life. “For the poor, children doubled as their only retirement fund. For the well-off, their children were still a kind of currency, in the rivalry among one’s friends and colleagues, and in the lifetime tally of success.”

Such goals become futile as parents approach end of life, and one character observes: “The prospect of death coming closer made you consider your life, what you wanted in what remained.”

Raising a child in harsh conditions, the need to sacrifice, Scarlett gains a new perspective on life and gradually comes to understand her mother’s tough ways. Valuing and using her ingenuity and setting firm priorities, Scarlett becomes more intent on giving to her immediate family and friends rather than taking.

Tuesday, January 18

Peril

Democrats and Republicans battle for the soul of the nation, a sentiment expressed by Joe Biden in a 2017 essay for The Atlantic. Astoundingly, the party that long claimed to uphold law, order, and family values embraced Donald Trump as its leader. Peril by Bob Woodward and Robert Costa details the final months of the Trump administration and early months for his successor, Joe Biden .

Trump’s goal as president was to disrupt government, and Biden's style is to restore expertise, competence and faith in government. With a style that is choppy even for journalists, the book details how the two men handle policy and crisis. Trump bullied and humiliated his staff, and the administration had a revolving door with four chiefs of staff, six national security advisors, and six defense secretaries in four years. Trump rejected allies and fellow NATO members while cozying up to troubling leaders of Hungary, Russia and North Korea.

Trump’s flightiness, cowardice about direct confrontations, and crazed anger over losses and stalemates may have been most apparent in his approach to Afghanistan. On November 11, four days after Biden was declared winner of the 2020 election, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff was surprised by a one-page memo on “Withdrawal from Somalia and Afghanistan.”

The memo, signed by Trump, had an unusual format. Quickly determining that the Defense Department staff, the national security advisor, and White House counsel were also unaware, General Mark Milley explained that Trump “signed something … without all the due diligence and military advice that I’m supposed to give him by law.”

The national security advisor soon alerted Milley that the memo was “a mistake” and should be nullified. Still, staff continued to worry that the volatile man could order all manner of military actions, even in his final hours, and many had little choice but to tiptoe around him, trying not to spark dangerous conflict.

Trump’s sole interest by January was convincing others that he had won the 2020 election. He renewed contact with Steve Bannon, a former advisor, who offered an ugly plan: “If Republicans could cast enough of a shadow on Biden’s victory…, it would be hard for Biden to govern. Millions of Americans would consider him illegitimate.”

Trump and some supporters pressed Vice President Mike Pence to reject certified electors from battleground states including Michigan and Arizona. Pence declined, after legal experts rejected such maneuvers. On January 5, the night before the joint session of Congress for certifying the election results, Trump ordered his campaign staff to release a statement that he and Pence were in “total agreement that the Vice President has the power to act.” Trump did not consult with Pence or his staff.

On the morning of January 6, Pence advised Trump that he was headed to the Capitol to do his job, and Trump whined, cajoled and pushed. Accustomed to getting his way, Trump had two expectations – for Pence to reject valid ballots and Congress to cave.

After Pence and Congress declared Biden the winner, many in Congress continue to remain wary. Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, recalling Nazi Germany, warned that Democrats could not take anything for granted after January 6. “Germany was one of the most cultured countries in Europe. One of the most advanced countries. So how could a country of Beethoven, of so man great poets and writers, and Einstein, progress to barbarianism?” Democrats must tackle the question, Sanders said, and the task is not easy.

Less than one quarter of the book is devoted to Biden’s presidency although the Trump section is sprinkled with reactions from Biden as candidate. Biden is simply less shocking.

One anecdote stood out, though, suggesting that Biden's staff overprotect and overdo for the president. Peril describes staff interrupting and joining a sensitive call between Maine’s Senator Susan Collins and the president – “Technology taking over, everyone on the line, running all their lives…. Another shadow over the shoulder of Joe.”

The book also describes Biden as holding firm to his principles, with a decision-making style that contrasts sharply with Trump’s.

Like Trump, Biden rejected a “forever war” in Afghanistan and a mission that “had shifted from its original intent.” Struggling with the “damned-if-you do, damned-if-you don’t” decision, Biden ordered a thorough review and announced the end of U.S involvement in the war less than three months into his presidency, fully understanding that the Afghan military, trained and supplied by the US military, might fail in defeating the Taliban.

By August 15, the Taliban stormed Kabul.

Throughout Peril, numerous leaders and political observers fret about Trump’s behavior, so much so that they become problems themselves. South Carolina Senator Lindsay Graham, who befriended the former president, explains: “Smart, rational people break when it comes to Trump. He’s not trying to get them to break. There is no magic. He’s just being him. And he wears you down. He’ll get you to do things that are not good for you because you don’t like him.”

It's one of the many reasons why voters should ignore Trump. Peril describes Graham’s repeated efforts to convince Trump to accept his loss in the 2020 election and move on. In one such exchange, Trump worried about losing his base. “They expect me to fight, to be disruptive.”

Trump’s supporters demand disruption even while claiming the United States is exceptional, the best country in the world. And there is the contradiction, embracing the country as superior, exceptional, untouchable even while doggedly pursuing disruption of its finest institutions, especially when their leaders refuse to capitulate to one highly flawed man.

Photo, courtesy of Alex Kent.

Saturday, January 15

Rescue

A 7.0 magnitude earthquake strikes Port-au-Prince in January 2010, a place already so desperately poor, prompting survivors to scramble to rescue loved ones and strangers and “to save photographs and whatever trinkets they held dear that meant nothing at all to anyone else on earth.” In the city’s poorest neighborhoods, and later in the refugee camps, people become the same, “were always the same,” and as one market vendor observes, this was “something we had always known from our low-to-the-ground perches…”

In What Storm, What Thunder by Myriam J.A. Chancy, ten

narrators, connected by blood and, in some cases, friendship share the story of

the earthquake and its aftermath. the stories are poignant and brutally honest. Often, small and seemingly inconsequential objects

and memories link the characters and the relationships they cherish. Even before the earthquake, all held

“dreams about where they’d rather be.” Individual methods may have varied,

including wealth, marriage, or crime, but the common hope is to escape hardship and grinding poverty.

Haiti ranks among the poorest countries in the world with a GDP per capita of less than $3000. Such poverty blurs individuality, and vendor Ma Lou, mother and grandmother of two narrators, describes the marketplace as a place of “colliding senses, … much of it decay, especially at the end of the day, when the best of what’s available is gone and all that remain are castoffs, the leftovers.” She describes the market workers as blending into the dust, becoming “one with the elements…, the nothing that we are.” She adds, “striving toward perfection is beyond our reach.”

Haitians who managed to flee prior to the earthquake learn the news by way of international broadcasts. Haunted and torn, they do not feel as they belong in their new homes: “Sometime, being an immigrant is like being illiterate,” explains one of the narrators. He feels the weight of the tragedy, knowing that up to 300,000 died and survivors endure unthinkable hardship – hunger, sexual assault, cholera, injuries while no medical treatment. Yet he also understands there is little he can do to help by returning home. “The weight of not being able to do enough,” Didier notes. “If I was honest with myself, that was why I’d left.”

The book lightly criticizes charity and donors who set

agendas for tackling crises, drawn into assisting others while seeking credit. Organizations

and donors judge needs while victims can only wait and accept whatever is given.

Of course, after the earthquake, Haitians required safe shelter, clean water and nutrition, yet what should be so easy, supplying basics, becomes overwhelming. And of course, individuals have needs and priorities less obvious

to others – a photograph of a loved one, bones of a deceased husband, the fading

memories of a child’s pattering footsteps, giggles and final kiss.

One of the most vulnerable narrators, a woman who loses

three children refers to NGOs as Not God’s Own. The

tent where she lives after the quake includes a label, “A gift from the

American people … in association with the Republic of Ireland” and she finds herself regretting dreams and plans made with a husband who abandoned her after the tragedy. “She wished they had other things in mind, escape routes and

exit strategies. They’d set their eyes on nothing but a future in which

everything would go according to a fabricated plan that they believed in more

than in reality itself – or that amplified it.”

Globalization of news, the instant knowledge about a distant crisis, might catch attentions briefly and that invites comparisons. Not long after the tragedy, one of the narrators, an architect, receives an email about an earthquake in the Italy and the loss of 200,000 rounds of pecorino. Activists quickly organize a global campaign to cook Italian recipes and donate proceeds to the region. “It was a kind objective, a goodwill gesture, but reading about it only made me sigh wearily,” notes Anne. “For every round of cheese, a person had died in the Haiti earthquake, and now I was expected to respond to this regional calamity while still burying our dead as if I, and others, might be ‘over’ what had happened to us….”

Still, the architect flounders in helping her hometown and

leaves for Africa, later putting her energy to entering an international

competition for rebuilding a Haitian cathedral near her neighborhood. She cares deeply about the project, describing the luxury of researching the history, exploring and imagining new beauty, while deciding whether her goal in creating a replacement is to

commemorate the dead or recognize what remains. Her section concludes: “I did

it for the satisfaction of doing something, of imagining a better, less hostile

future, where a God might still exist to watch over us.”

As pointed out in Allure of Deceit, no amount of rules and regulations can prevent the ambition, greed, judgment, control, or inequality that can accompany organized charitable giving.

The publication of What Storm, What Thunder, a work of fiction, was timely as another earthquake, magnitude 7.2, struck Haiti in August 2021, about 70 miles away from the capital, destroying more than 60,000 homes and killing more than 2,000 and injuring 12,000.

Tuesday, December 28

Pointing out the obvious

Society often ostracizes its most extraordinary children. Bewilderment by Richard Powers is set in the near future in a bleak world of irreversible climate change with constant reminders of the habitat loss and environmental stress. The US is caught up in a downward autocratic cycle, as citizens resist a government that becomes increasingly more repressive, impatient with any who are “different.”

The story follows one small family who cares about neglect of the planet. Robin, nine years old, is often frustrated, hurt and angry, bursting with observations and questions even while determined to understand and follow in the footsteps of his activist mother who died when he was seven. Theo, an astrobiologist, raises the boy on his own, distraught over his many parenting errors. Classmates consider Robin “weird” with teachers urging medication and treatment: “I never believed the diagnoses the doctors settled on my son…. The suggestions were plentiful, including syndromes linked to the billion pounds of toxins sprayed on the country’s food supply each year…. Oddly enough, there’s no name in the DSM for the compulsion to diagnose people.” Theo cannot imagine “Robin toughening up enough to survive this Ponzi scheme of a planet.”

After the school suspends Robin for punching another child, Theo takes the boy on a camping trip in North Carolina where he and his wife had honeymooned. And he makes plans to enroll the boy in experimental treatment, similar to biofeedback, using recordings provided by various human subjects including his mother. Over the weeks, Robin absorbs her intelligence, ambition, cheerful optimism and unlimited empathy for all living beings, no matter how small, including “systems of invisible suffering on imaginable scales.” Robin increasingly speaks out for the planet and voices her concerns in eerie ways. At one point Robin tells his father “there’s no point in school. Everything will be dead before I get to tenth grade.” The father concedes that the “Decoded Neurofeedback” was changing his son “as surely as Ritalin would have. But then everything on Earth was changing him. Every aggressive word from a friend over lunch, every click on his virtual farm, every species he painted, each minute of every online clip… there was no ‘Robin,’ no one pilgrim in this procession of selves for him ever to remain the same as.”

The pronounced progression, similar to that of the experimental subject in Flowers for Algernon, unnerves Theo. He worries about Robin getting along in a world where so many “lived as if tomorrow would be a clone of now” and understands “In the face of the world’s basic brokenness, more empathy meant deeper suffering.”

Robin sees too clearly that humans collectively are “breaking the whole planet” and “pretending they aren’t.” He tells his father, “Everyone knows what’s happening. But we all look away.” Yet Theo suspects that resistance may be impossible against the billions who bask in delusions and can only conclude, “Oh, this planet was a good one.”

The book is reminiscent of Interruptions, about a twelve-year-old boy. Gavan is well-read and full of questions about the world, tolerating neither hypocrisy or assertive ignorance, and teachers urge the parents to put the boy on Ritalin. His mother, while admitting that the boy has a knack for finding trouble, vehemently resists. Gavan convinces his best friend to skip school and follow a project engineer into the forest, hoping to collect evidence that might stop construction of a cross-island road. A brutal murder follows, and mother and child work separately and at cross purposes to expose secrets about an unnecessary road that would forever change the character of their Alaskan community.Some children point out the obvious. “As children grow up, the memories and stories of childhood become myths. The details shape a child’s life, providing motivation, hope and comfort as life grows more complicated.”

Monday, November 29

Imagination

Double Blind starts strong, but character and plot development struggle by the novel's end. Still, Edward St. Aubyn masterfully explores many of the themes found in Fear of Beauty and Allure of Deceit including philanthropy, the human desire for control, and the corruption of immense wealth.

Francis is an ecologist, intent on returning large patches of land to the wild. He meets Olivia at an Oxford conference and immediately falls in love: “They had only spent one night together, but it had the tentative intensity of a love affair rather than the practiced abandon of hedonism.” The couple assists Olivia’s good friend, Lucy, who discovers she has brain cancer shortly after starting a new position finding worthy innovations for her billionaire boss, Hunter. Hunter is spoiled, surrounded by sycophants and regularly fueled by drugs until he falls in love with Lucy.

Olivia and Francis start spending time with Lucy, Hunter and wealthy friends – and the book’s easy banter examines how Hunter and other philanthropists influence career scientists, and the more forthright scientists can temper impulsivity, waste and extremism. When Hunter first meets Lucy and tells her about his foundation, she responds: “To a foreign eye, America has so much philanthropy and so little charity. Most people have to kill themselves to prove that they deserve ordinary kindness, while a tiny group of people never stop boasting about how generous they are – as long as it’s tax-deductible.”

Like Allure of Deceit, the book captures how charity is more about donor image and contentment than support for recipients. Early on, Hunter is interested in funding only big, splashy ideas and he dismisses problems like schizophrenia because the illness only affects 1 percent of the population, most of whom are poor. Lucy rejects such thinking, but she, too, is impatient with science’s narrow specializations, mindless quests for tenure and secure funding.

Olivia is the most traditional and serious scientist of the group while Francis may be the most intellectual, at one point noting “The point was not to assert beliefs, but to remove the rubble of delusion that constituted almost all beliefs.” Yet he remains defensive about the anecdotal nature of his research and meager income. He is annoyed by career biologists, alluding to the depressing work of documenting the decline of species and referring to dissection labs as “random murder.” In an early conversation with Olivia, Francis - who felt “the weight of ecological doom … sometimes so great that he had felt the pressure of misanthropy and despair” early in life - “couldn’t help noticing the strangely cheerful, almost rivalrous way they had discussed the death of nature.”

When Olivia and Francis first fall in love, he expresses aspirations similar to those of Henry David Thoreau, and she expects him to devote the most time caring for their expected child. But wealth, career recognition and control are alluring, and Francis succumbs to the temptations presented by another billionaire who donates a massive sum to an international ecology project that she expects Francis to lead. The relationship between Francis and Olivia may not survive his constant introspection about the human role in natural wilderness – and his tendency of “identifying with one non-human animal after another.” But Olivia is practical: “babies weren’t born to redeem or justify other people’s lives, they were born to have their own life.”

In the end, a schizophrenic twin may express more contentment and self-awareness than the most educated characters. That man has secured his first job working in a kitchen, funded by – of course – another wealthy philanthropist who lost his own son to suicide. The young man's goal is pursuing a life that comes close to being ordinary with the ability, as Sigmund Freud once wrote, to transform “hysterical misery into common unhappiness.” At one point, the schizophrenic character tells his therapist: “Sometimes things are more powerful when you know they’re not true, because you have to imagine them so hard….”

A determined imagination is useful in setting life goals and finding contentment.

Monday, November 15

Freedom

A Song Everlasting by Ha Jin tells the story of an accomplished singer who angers the Chinese Communist Party and relocates to the United States where he performs occasionally for low wages and struggles for a green card while taking on odd jobs of tutoring students and laboring with a construction crew. His new life requires separation from his wife and daughter, flexibility and humbleness. Still, Tian hopes to find artistic freedom and hopes for his daughter to attend a US college.

The haunting and eloquent book may move too slowly for some readers as Tian compares his career and life in China versus that in the United States, exploring the multiple meanings of freedom when intertwined with comfort, trust, security, responsibility as well as the quest for a meaningful life.

Early on, Tian claims to have no interest in politics and hopes that his superiors might forgive him and plead for his return. Instead, he learns the party has a long reach through the diaspora in the United States, intent on ostracizing him if they cannot keep him under their control on their terms. And a good friend points out, “Freedom is not just a personal choice – it’s also social conditions.”

For Tian, separated from his family, freedom comes to mean solitude and isolation. Chinese government contacts argue that freedom is worthless if one must go hungry and live apart from loved ones, and Tian agrees that “freedom is a different kind of suffering away from tyranny.” He admits that freedom can be “frightening and paralyzing,” taking time to get used to, yet he worries that “cultural pragmatism” limits Chinese people’s visions and pursuits. He misses his celebrity status and the many associated favors while also embracing anonymity. He eventually determines that “solitude is a path to freedom, for which you must accept everything that happens to you, including hunger, disease, and even death. You’re supposed to be responsible for your own existence, body and soul.” At another point, he notes: “To be left alone – that is the essence of freedom.”

Over the course of seven years, he wonders if the separation and suffering are worthwhile, if the sacrifices are really necessary and justified, and for Tian the answer remains a steadfast yes, as he recalls words of his father-in-law – that courage is “manifested in the way one lived and worked every day.” By the end, Tian is a fervent and thoughtful advocate of democracy, suggesting: “It was time to remind people that democracy must not retreat any further, or the Chinese government would export its system of digital autocracy to control and dominate the world.”

Freedom of thought is a fundamental human right, nurtured by formal education and self-education. The American Library Association points out that "censorship, ignorance, and manipulation are the tools of tyrants and profiteers" and true justice and freedom depend on the constant appreciation and exercise of such rights.

Thursday, October 28

Self-deception

The novel Where the Truth Lies from British author Anna Bailey demonstrates how a community or individual can use religion as a weapon to control or belittle others. The book is set in small rural Colorado town, where a father regularly abuses his three children, insisting that God made him the way he is and God “understands why I’ve done the things I’ve done.” Of course, that argument does not apply to others who may choose to live differently, whether that might be homosexuality or immigration.

For the fundamentalist father, his way is God’s way, the only way, and a cycle of cruelty, humiliation, guilt, anger and shame ensues. Expectations of rote forgiveness mock Christian principles. Teenagers observing and subjected to such abuse lash out against the unreasonable controls and expectations with self-abuse – shutting down with self-loathing, substance abuse, sexual debasement. Hurting one’s own body “feels like power, the way a mad king might slaughter his people, just to prove he can.” Resorting to extreme behavior is perhaps a last-ditch effort for finding someone who might care. If that savior does not emerge, then a life with so much anger and control is not worth living anyway.

Children trapped in such situations, expected to honor insane parents, cannot help but question whether God even exists. In this book, young Jude protests that "God wouldn’t –" and his brother Noah responds: “This has nothing to do with God, you idiot. God doesn’t do anything, He just whispers in people’s ears that they’re worth jack shit, and they pray and pray hoping He’ll stop, but He doesn’t, and in the end they just go crazy. That’s all God does, He makes people go crazy, so get that into your head and grow up!”

Most adults in the small town express sympathy but then shrug and look the other way. The worst of it is when family members turn on one another, pointing out transgressions, some true and others false, finding scapegoats for the tyrant to attack. The goal is to deflect attention away from their own wrongdoings or create horrific chaos so that others outside the family might intercede.

The book's title, Where the Truth Lies, reflects the multiple meanings of the verb “to lie” as detailed by Merriam-Wesbster: to engage in falsehoods, to sleep or remain motionless, to remain inactive or in hiding, to bed with, to have an effect, to remain still, to belong or to be neglected. Of course, there is but one meaning for truth - what happened to Abigail Blake and why.

Bailey’s novel supports the notion that an outsider can sort through carefully crafted myths, history and expectations and reveal our true natures.

Self-deception, the embracing of false beliefs despite evidence to the contrary, leads to horrific behaviors and crimes. Self-deception is both morally wrong and morally dangerous, individually and collectively. Those who engage in self-deception, evading evidence to avoid knowledge and truth about real problems swirling in their midst, cannot be trusted on any topic.

Collective self-deception is especially dangerous, and yet the growing trend, fueled by the internet and social media, “has received scant direct philosophical attention as compared with its individual counterpart,” notes the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The self-deceived turn to groups who reinforce their beliefs and most frightening: “Compared to its solitary counterpart, self-deception within a collective is both easier to foster and more difficult to escape, being abetted by the self-deceptive efforts of others within the group.”

Monday, October 11

Stories and myths

the series of events in a book, film or play

story from ancient times, especially one that was told to explain natural events or to describe the early history of a people

Firuzeh’s family flees the threats of Afghanistan, traveling to Australia by way of Pakistan, Indonesia and Nauru in On Fragile Waves by E. Lily Yu. Hope quickly turns to despair as the young woman observes the refugees around her resort to lies and bullying, prostitution and suicide. Firuzeh does not know how to respond when pressed about why the family left, and a doomed friend retorts, “We need reasons like we need water or air…. I’ll find you your reason.”

Experienced refugees warn that Australia is cruel, lonely, hard. After a lengthy process of confirming citizenship, the government offers families $2000 and plane tickets to return to Kabul. Only refugees who persist through the delays and indignities make it to Australia, and a prostitute reminds Firuzeh that those who still treat others with kindness, even after repeated pain and humiliation, are wealthy. Others, including the Australians who fear and resent the refugees, are poor.

Beauty and creativity can be found even in hardship. Early on, the family tells favorite stories to entertain and inspire one another. Only a few stories reach the status of myth. “There’s something about beginnings and endings,” explains Firuzeh’s imaginary friend. “That polishes them so smooth you nearly see your face in them. Then you open your hands and let them go, and the current pulls you onward and way. Behind you, those stones sink down to the mud, where no one will ever find them again.”

Individual tales of hardship go quickly forgotten for Australia's policies nad public opinion. Firuzeh’s family receives a TPV – a temporary

protection visa – without understanding the consequences of a three-year

stay. A few Australian teachers understand that such visas are “inherently destabilizing” for children absorbing a new language and culture.

Others resist examining the deeper

consequences:

‘I don’t

think our government would do anything evil. Besides, isn’t Afghanistan safer these

days? With the Americans there, and everything?’

Mr. Early

said, ‘I haven’t heard much in the news lately.’

‘That’s good,

isn’t it?’

The refugees endure long waits to enter Australia and start a

new home life. E. Lily Yu details the meager rations and crowded conditions of refugee camps, with

guards freely dispensing sleeping pills and other psychiatric medications to

ease boredom and maintain order among detainees. “Sleeping is an easier way to

wait,” notes one character. “All of us had something to wait for, and that kept

us going…. Now the minutes of our lives are wasted. Time scrapes our nerves.”

Never-ending hardships replace the hopeful storytelling. “What a story, your family’s,” observes

Firuzeh’s imaginary friend. “Over and over, without an end.” Firuzeh admits she

does not like how her family’s story is going and Nasima suggests “You can

change it…. If you want. If you’re brave. If you remember how.”

Family cohesion crumbles as the couple and two children lose respect for one

another. Upon learning about their temporary status, the mother urges the

father to take action while Firuzeh insists their father is a hero who will

think of something. The argument intensifies, the father blaming his wife for

working and neglecting the children while she criticizes him for

weakness and men's habit of blaming problems on wives. The wife repeats her mother’s

assessment that hers husband is a frightened boy, not a man, and the Firuzeh’s father

strikes her mother.

Firuzeh, who always admired her father, lashes out, telling

him she hates him and wishes him dead. The

man weeps, wondering how his more assertive wife and children will ever survive

in dangerous Afghanistan.

Of course, such tragic scenes unfold daily in the camps and neighborhoods where refugees try to start anew, so common that most fail to notice their own role in the dangers of routine cruelties and entrenched inequality.

The anger and recognition of temporary status changes the world for Firuzeh and her brother who runs away. Searching for him, she boards a train full of happy students,

“holding bookbags as shields, laughing and shoving each other. Firuzeh hated

them wit ha black and overwhelming passion. Not one of them had to worry about

deportation, or a missing brother, or a broken mother…. ”

The father takes desperate action, giving his family a

reprieve, and Firuzeh contemplates how the stories of Australia differ from those

of Afghanistan and wonders if they are still useful. The imaginary friend reminds that “Stories go where people go….

In dreams, in fresh tellings, in memories.”

Taking control of one’s story, sensing how others respond and making adjustments that suit the author and her audience, can make all the difference in surviving the life we're handed. And we won't recognize that the making of a myth is underway, and our own role, until long after the fateful conclusion.

Tuesday, September 7

Left unsaid

“No one is truly voiceless, he whispered, either they silence you, or you silence yourself.”

After fleeing Aleppo and enduring a traumatic journey

separate from her family, a young Syrian woman lives in a London apartment from

which she observes daily routines of her neighbors. She does not speak and

embraces privacy, an instinct for self-preservation.

Silence Is a Sense by Layla Alammar reflects the constant comparisons and contradictions of the refugee experience – the comfort and annoyances of tradition, the discoveries and puzzles of another culture, the curiosity and ignorance and assumptions of new companions, the guilt over fleeing one’s homeland, doing anything to survive and not knowing what happened to those left behind. Tyrants, whether in Syria or London or Kabul, fear comparisons. As observed by the protagonist of Fear of Beauty: “Those who prefer continuity avoid comparison and regard any hint of choice as criticism. New interpretations from others might twist opinions in unknown ways.”

The protagonist writes her thoughts as a refugee for a small newspaper, under the pseudonym “Voiceless.” She initially resists the editor’s requests for more memories and experiences. “Everybody here wants a story,” she notes. “They all want stories – how did you get here? How long did it take? How easy was it to process your papers? … They want to hear about the hardship and the struggles and the people who died along the way.” She worries that her more liberal-minded editor and readers have an agenda, wanting “to see, in me, all the hopes and ills and frustrations and struggles and singular stories of some five million plus people. They want me to speak for the chaos of the world…” She finds that “The human need for stories is itself an obstacle to memory. Like our dreams, we are not content with images or scenes or fragments of sensory stimuli… We try to place these elements within a structure that makes sense, wading back through fragments, trying to stitch it all together into a coherent pattern – a beginning, a middle, and an end.” Stories are never so easily completed, and the protagonist feels “persecuted by the things I remember and by what my mind chooses to hide from.” She suspects that the most common routines may have been forgotten or blended into one memory: “It seems to me that complicit in the very idea of memory is actual forgetting.”

Memories meant to be cherished are reviewed over and over

again until they become rote, over-practiced even while blending with new awareness

and perspectives. Efforts to vanquish the most horrific memories, piercing again and again with renewed vigor, are useless. All shape her character, and she embraces literature and poetry,

such as that of Edgar Allen Poe, because “There is someone out there who has

been gripped by fear and loathing as I have.” Emotions

may take precedent over actions in the most enduring memories, and it may be possible that life's most beautiful moments escape notice, failing to be preserved by memory.

London is supposed to be safe, but refugees confront discrimination and hatred, and the character expresses pessimism about the naïve notion that education might overcome hatred, an error “repeated on the news, in op-eds, in documentaries, in social media posts. There’s this idea that if only you bombard bigots with enough facts and data and statistics, you can cure them.” The problem is not lack of education, she maintains, but “fear of the unknown, the Other, fear that things are changing in ways he can’t predict or control.” Of course, change is inevitable for any society, with or without refugees.

The protagonist finds that memories presented as stories lure “the

public into caring about things and Others they might not otherwise care

about.” Stories carry listeners to other places, helping them understand other cultures and perspectives,

and thus do “make migrants of us after all.”

Some of the most powerful stories go untold. They might be too unbelievable or, in this case, a writer is “terrified that a story will diminish the real, that it will cheapen the experience beyond what I can bear.” The protagonist cautions others to examine the gaps in many tales, the questions that no one asks and the answers that remain hidden inside another person: “That’s where the story is.”

Tuesday, August 24

Need for expertise

As suggested by this blog's "Functional leadership?" and "Key to success," the Taliban cannot afford to lose the most talented, educated Afghani citizens.

Al Jazeera reports today that the Taliban are urging the United States to stop evacuating skilled Afghans, such as engineers and doctors. “We ask them to stop this process,” spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid said at a press conference in Kabul. “This country needs their expertise. They should not be taken to other countries.”

But like most fundamentalists, the Taliban will reject "expert" opinions on sensible education programs and public policies. Skilled agriculture specialists don't want to grow poppies. Modern health providers may support women's reproductive rights and family planning. Computer scientists do not want to collect or abuse citizen data. Weapons specialists won't want to target former international colleagues. Chemists and physicists will struggle to develop religious rationales for scientific phenomenon and limited resources. Engineers focus on math and lack time for theological rhetoric.

The educated, fully aware of Taliban's past disdain for education, will balk at working for the extremists. "Insurgencies the world over, from the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka to Boko Haram in Nigeria, have sought to attack, resist, influence or control access to and the content of education," notes "Taliban Attitudes and Policies Towards Education" by Rahmatullah Amiri and Ashley Jackson for the Centre for the Study of Armed Groups. "However, the Taliban’s level of interference, and the growing sophistication of its approach, sets it apart. It has developed a series of policies and bureaucratic guidelines governing education provision and established a shadow education ministry, with education shadow ministers at provincial and district level and monitors charged with overseeing schools in Taliban areas."

Key aspects of Taliban attitudes that will conflict with education that creates expertise:

-a preference for Islamic religious education, with the group divided between traditionalists and those who recognize the need for modern approaches;

- reluctance to acknowledge women's capabilities or allow mixed-gender workplaces and teams;

- opposition to donor conditions on human rights and women's rights, even though the country's education system heavily relies on international aid.

In December 2020, the Taliban negotiated an agreement with UNICEF to operate 4,000 classes in areas then under its influence. "That the Taliban is willing to negotiate a national agreement with a UN agency demonstrates its desire for aid – and international recognition," note Amiri and Jackson, adding that "the Taliban is increasingly seeking to position itself as capable of governing. Some segments of the insurgency’s leadership acknowledge that Afghanistan needs a diverse, modern education system. They also understand that, if they want external recognition and political legitimacy, they will have to make concessions on some of their more hardline positions, particularly on female education."

Taliban policy documents on education are clear - the group intends to regulate, control and influence all forms of education, including "what subjects can be taught and who can attend school."

True education requires critical thinking, which naturally lead to questions and doubts about fundamentalism and extremism. Ruthless, primitive policies that counter best practices are not sustainable. The writers concede that "Education is inherently political, and governments and armed groups the world over have long used the education system to indoctrinate, surveil and regulate the behaviour of the population."

The educated will balk at working for a Taliban government that does not value freedom of thought that goes hand in hand with the best education programs. Many skilled Afghanis anticipate coercion, and the International Labour Organization describes forced labor: "work that is performed involuntarily and under the menace of any penalty. It refers to situations in which persons are coerced to work through the use of violence or intimidation, or by more subtle means such as manipulated debt, retention of identity papers or threats of denunciation to immigration authorities."

That is why thousands of Afghanis gather at the Kabul airport, willing to sacrifice all to flee the country.

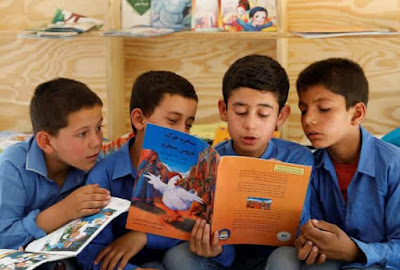

Photo of US Air Force C-17 Globemaster III transport aircraft, evacuating more than 600 Afghans to from Kabul, courtesy of Al Jazeera and Defense One; photo of library, courtesy of the American University of Afghanistan.

Friday, August 20

Functional leadership?

Taliban leaders are desperately trying to send signals to the foreign media that they can improve governance and bring order to Afghanistan. But good governance requires good communications which rely on strong reading and critical thinking skills.

Leaders lacking such skills will only deliver frustration, as suggested by Ian Pannell reporting for ABC News.

Pannell and his team had permission from Taliban commanders to head to the airport. Stopped at a checkpoint, shown at the 3-minute mark in this video, the Taliban fighters stopped the crew, staring blankly at a letter from Taliban command. Amid shots being fired, the Taliban then turned the reporters away.

"These guys can't read," said Pannell, clearly frustrated. "The agony of not being able to get to the airport, past Taliban-controlled checkpoints, is the reality on the ground here."

The Taliban face a big challenge with the demographics of the country's 38 million people. The median age of the population is 18.6. So more than half the people were not around in 2001 when the Taliban last ruled the country and have no recollection of the harsh edicts based on arbitrary interpretations of Islamic writings. Women also make up half the population, and many bitterly oppose Taliban policies forcing subservience to male relatives, arranged marriages at early ages, and bans on a female presence at schools and work,

One might wonder why the Taliban would desperately try to prevent Afghans who despise such policies - some of whom might organize formidable resistance - from fleeing the country.

A key reason is that much of the country still suffers from illiteracy and functional illiteracy. Since 2016, the literacy rate in Afghanistan increased by more than 40 percent, reported UNESCO in March 2020 report. Still, the literacy rate is 55 percent for men and about 30 percent for women.

Such high rates of illiteracy offers an explanation for the "wholesale collapse" of the Afghan military in defending the country against the Taliban. "[P]erhaps the biggest hardship was having to teach virtually every recruit how to read," suggested Craig Whitlock in the Washington Post, and "only 2 to 5 percent of Afghan recruits could read at a third-grade level despite efforts by the United States to enroll millions of Afghan children in school over the previous decade.... Some Afghans also had to learn their colors, or had to be taught how to count."

The Taliban may have overtaken the country - along with a sizable cache of planes and artillery from the US and other foreign governments - but many of their fighters lack the skills to use the high-tech equipment. Hence, the Taliban have blocked borders and demand that neighboring countries return fleeing Afghan soldiers who worked side by side with US and NATO troops. More than 500 Afghan soldiers fled to neighboring countries including Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, using US-supplied planes and helicopters, reports the Hill. Uzbekistan has since returned some of the refugees, after the Taliban offered security guarantees, reports Reuters. Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan express concerns about admitting refugees, some of whom could be fighters in disguise or extremists, reports Al Jazeera.

The Taliban also desperately need many Afghanistan's government workers for now, hoping to harness top minds and talent to sort through an array of policies and finances, everything from tracking down revenues and foreign aid to arranging new partnerships and favorable contracts for infrastructure and the sale of resources like rare-earth materials.

So, the Taliban tolerates the foreign press for now, striking a "conciliatory tone," hoping to prevent mass panic and protests by emphasizing a smooth transition. The leaders continue to claim they will take no retribution against the many who supported the US presence over the past two decades.

A handful of courageous people, reporters like Pannell and Afghan citizens on social media, document the tense transition, and Taliban leaders will struggle to appease a populace that has become accustomed to more freedom and opportunities over the past 20 years than the the new regime may be prepared to provide.

Screenshots of Taliban handling a letter authorizing entry to the airport near Kabul and Ian Pannell, courtesy of ABC News.

Thursday, August 19

Key to success

When our world offers troubled news, many of us embrace fiction – sometimes for escape and sometimes to understand the human response to massive political, economic and cultural trends.

The ability to read is a treasure and so is the wealth of stories from around the world.

Read NZ Te Pou Muramura recognizes that illiteracy is a treacherous condition in the modern world, and the not-for-profit group based in New Zealand promotes literacy for multiple reasons, especially functional literacy:

• Increasing demands of society and work require citizens to “be able to read a wide range of information to function effectively at work and everyday life.”

• About 40 percent of adult New Zealanders lack the literacy skills needed to participate fully in the society and economy, and an OECD

• Reading, especially for pleasure, is “critical" for a nation’s prosperity and well-being.

• Reading for pleasure is a more important factor in determining “a child’s education success than their family’s socio-economic status.”

The functionally illiterate do have limited ability to read, write and do calculations, and most do not enjoy applying such to everyday tasks. An OECD survey of member countries suggested that "between 25% and 75% of the respondents aged 16 to 65 did not have a literacy level considered 'a suitable minimum skill level for coping with the demands of modern life and work." The dangers: A cleaning or construction crew might misunderstand directions and mix the wrong chemicals. A caregiver may make a medication error. Customers miss unreasonable terms in a contract for an appliance, car or home. A government official might overlook an obvious policy solution to a community environmental problem. Corruption thrives in societies with low literacy rates.

Reading - often and for pleasure - is the cure. In that spirit, the organization in New Zealand offers weekly “prescriptions” each week from the Reading Doctor. Louise O’Brien, editor and reviewer with a doctorate degree in English literature, also conducts interviews and answers reading-related questions.

The organization launched the blog in 2020 amid the Covid-19 pandemic, and an early prescription was for books that “soothe and comfort.” At that time, Wells urged readers to re-read old favorites:

“Books have the power to distract us from the here and now, to amuse and occupy us, as well as to soothe and comfort. Reading is an activity ideally suited to quiet solitude, so, if you’re in isolation, turn to a book for company and reassurance.

“What’s more comforting than re-reading, returning to a much-loved book, opening covers which feature in our memories, turning pages we’ve dog-eared ourselves, being lulled by the familiarity of a well-known story inhabited by old friends.”

This week the Reading Doctor offers suggestions for books about Afghanistan. “It’s easy to forget, amidst the chaos, fear and violence of current events, that Afghanistan is also a country of poets and artists, with a rich history and enormous beauty, and that those fleeing their homeland must leave a great deal behind them.”

It’s an honor for one of my books t o be included in this week’s prescription: “The politics of Western charity and intervention in war-ravaged Afghanistan is the backdrop for Allure of Deceit by Susan Froetschel, in which suspicions of fraud and murder follow the mysterious disappearance of a group of aid workers.”

Fear of Beauty, also set in Afghanistan, explored one woman's desperate quest to learn to read. Banned from classrooms, Afghan women had high rates of illiteracy under the previous Taliban rule, which ended with the US-led invasion in late 2001. Since 2016, the literacy rate increased by more than 40 percent, according to UNESCO in a March 2020 report. Still, the literacy rate is 55 percent for men and about 30 percent for women. Reading is the key to new ideas and success, and Afghanistan's readers will resist bullying, authoritarian efforts to dismiss this essential skill.

Books both inspire and record individual dreams, and offer a reminder about how the Taliban will struggle to convince Afghanistan’s 38 million people that reading and education are worthless endeavors.

Photo courtesy of Mohammad Ismail/Reuters and the Guardian.