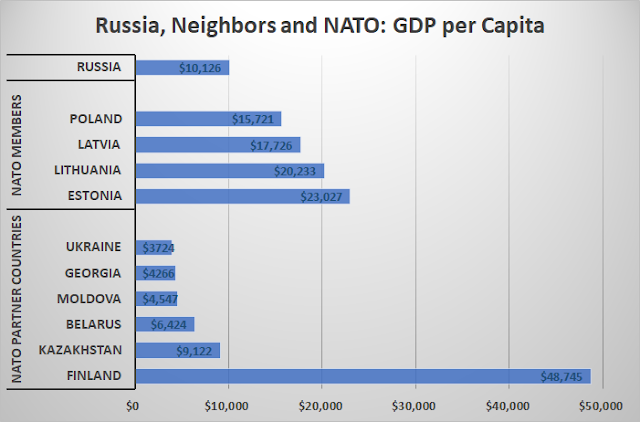

Data on GDP per capita is from the World Bank.

Monday, February 28

Neighbors

Thursday, February 17

Inequality

The Glass Kingdom, creepy and suspenseful from the start transforms to simple horror by the end, masterfully detailing the resentments that emerge over inequality and the ways that individuals justify stealing from others: “It was a war between herself and the moneyed classes, and in that war all ruses were legitimate, all feints justified,” concludes Sarah soon after creating and selling a set of forgeries, presented as correspondence from her most recent employer, a famous author. Committing a crime eliminates social protections, and when encountering trouble later, Sarah cannot turn to authorities: “It was too late, in any case, to become an upright citizen and call the police.”

A reader

must suspend belief about the plot and numerous character decisions. Why would

the author retain her own handwritten letters to celebrities like Angela Davis

or Diana Vreeland? Why would collectors sell them to the author and not to the other

collectors seeking them and paying a premium price? Wouldn’t the collectors have

direct dealings? And Sarah’s transport of a couple hundred thousand by air, crossing

international borders, would surely be much riskier with more challenges than

described.

Then again,

people are odd, sometimes extraordinarily lucky or unlucky as the case may be. And

loneliness – so familiar during the Covid pandemic – compounds the poor

decision-making displayed throughout the novel: “The burden of that solitude

had begun to crush her hour by hour.” Sarah fails to recognize the assuming manipulations

of a new friend Mali who requires assistance in covering up another crime, not posing questions or objections after Mali suggests: “Let’s do it my way, OK?

I’m sorry to get you involved, though,” quickly adding, “We’d both like that, no?” Finally, why would a young woman not quickly abandon a hotel losing

guests, let alone a city with increasing civil unrest?

The dark and

moody novel powerfully demonstrates how inequality makes trust or mutual respect

impossible. Characters are divided not only by wealth and skill, but ethnicity

and religion. A hotel maid concludes that the farangs, referring to foreigners, are “animals in their hearts, untouched by the grace

of Lord Buddha” – and they exist in a “prison of their own making, and she

entered that prison only to make a living. For in the end there was no other

reason to enter it at all.”

The book conveys that life is unfair at every level. Highly visible, cruel inequality ensures that sinister unfairness and corruption never end.

Wednesday, February 16

Memories of love

The Parted Earth is a family saga that begins with the 1947 Partition of India. A teenager, Deepa, observing and worrying how New Delhi and neighborly relations can change violently in a short period of time, recalls a comment from her mother: “People are inherently good… they’re just not inherently good all of the time.” The comment ominously foreshadows the ethnic hatred and violence of the Partition, turning neighbors against neighbors and even some parents against children, as noted by Stanford’s Partition Archive:

“Up to two million people lost their lives in the most horrific of manners. The darkened landscape bore silent witness to trains laden with the dead, decapitated bodies, limbs strewn along the sides of roads, and wanton rape and pillaging. There was nothing that could have prepared the approximately 14 million refugees for this nightmare. The 1947 Partition of the Indian subcontinent into the independent nations of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan was accompanied by one of the largest mass migrations in human history and violence on a scale that had seldom been seen before.”

The book begins sweetly, taking on the tone of a young adult novel while describing the happy life of Deepa, the only child of two progressive physicians. But violence and chaos mark the summer of 1947 with India on “the verge of a war with itself.” The brutality and separations haunt survivors long afterwards, lingering for generations. For those who witnessed the atrocities, “Distance and time were inconsequential.” Collective grief ensures loneliness, trust is fragile, and parents struggle to explain events to their children. Withholding information about a child’s father, conceived during the chaos, is cruel. Learning horrific truths about a parent’s role in atrocities is perhaps even worse.

Deepa bears a son, Vijay, who searches for the father he never met and answers about his mother’s resentment. A search in India and Pakistan separates him from his daughter, Shanti, who is 10 and raised in the United States.

Every character, during the days of Partition and long afterward, is left feeling as if he or she could have done more – displayed more grace, more compassion, more patience.

Unlikely friendships that cross generations and cultures bring comfort, new perspectives and even rescue. For Vijay, it’s Miss Trudy – his mother’s friend who cares for him and treats him as her own. His mother was stern, ensuring completion of homework, assigning extra math problems to do and books to read, providing shelter and food. Yet “Miss Trudy taught him how to make dough rise for bread, how to sew on a button, how to draw a dragon, kick a football…. She tended to his skinned knees, comforted him when his classmates called him a half-caste bastard. Miss Trudy let him be weak, so that when his mother picked him up in the evenings, he could pretend to be strong.”

Deepa is furious after Miss Trudy poses the boy's questions about Vijay’s father. More than anything, Deepa feels “betrayal… sudden understanding about the special closeness her son shared with his babysitter, instead of his own mother.”

Years later, Shanti, wonders why Vijay, her father, was so distant, spending so much time in India. In her forties, she forms and embraces a friendship with an elderly widow next door, whose husband committed suicide, and the two women share details from their pasts.

Sharing stories and close listening pays dividends as Shanti finds the widow’s husband on a website that documents Partition experiences, and the widow locates the sister of Vijay’s father, Shanti’s grandfather, in Pakistan.

Planning for Partition and the aftermath with mass migration, surging resentment and violence, spanned a few months, but the rebirth, renewal, and forgiveness required years.

Shanti spent only a few days at a time with her father, but is grateful to have known his love. “She didn’t have it for long enough. But now, in her forties, she felt it stronger than ever. She would hold on tight to it and never let it go.” Love, however brief, is embedded in memories, providing strength to trust and care for others even while handling loss.