When our world offers troubled news, many of us embrace fiction – sometimes for escape and sometimes to understand the human response to massive political, economic and cultural trends.

The ability to read is a treasure and so is the wealth of stories from around the world.

Read NZ Te Pou Muramura recognizes that illiteracy is a treacherous condition in the modern world, and the not-for-profit group based in New Zealand promotes literacy for multiple reasons, especially functional literacy:

• Increasing demands of society and work require citizens to “be able to read a wide range of information to function effectively at work and everyday life.”

• About 40 percent of adult New Zealanders lack the literacy skills needed to participate fully in the society and economy, and an OECD

• Reading, especially for pleasure, is “critical" for a nation’s prosperity and well-being.

• Reading for pleasure is a more important factor in determining “a child’s education success than their family’s socio-economic status.”

The functionally illiterate do have limited ability to read, write and do calculations, and most do not enjoy applying such to everyday tasks. An OECD survey of member countries suggested that "between 25% and 75% of the respondents aged 16 to 65 did not have a literacy level considered 'a suitable minimum skill level for coping with the demands of modern life and work." The dangers: A cleaning or construction crew might misunderstand directions and mix the wrong chemicals. A caregiver may make a medication error. Customers miss unreasonable terms in a contract for an appliance, car or home. A government official might overlook an obvious policy solution to a community environmental problem. Corruption thrives in societies with low literacy rates.

Reading - often and for pleasure - is the cure. In that spirit, the organization in New Zealand offers weekly “prescriptions” each week from the Reading Doctor. Louise O’Brien, editor and reviewer with a doctorate degree in English literature, also conducts interviews and answers reading-related questions.

The organization launched the blog in 2020 amid the Covid-19 pandemic, and an early prescription was for books that “soothe and comfort.” At that time, Wells urged readers to re-read old favorites:

“Books have the power to distract us from the here and now, to amuse and occupy us, as well as to soothe and comfort. Reading is an activity ideally suited to quiet solitude, so, if you’re in isolation, turn to a book for company and reassurance.

“What’s more comforting than re-reading, returning to a much-loved book, opening covers which feature in our memories, turning pages we’ve dog-eared ourselves, being lulled by the familiarity of a well-known story inhabited by old friends.”

This week the Reading Doctor offers suggestions for books about Afghanistan. “It’s easy to forget, amidst the chaos, fear and violence of current events, that Afghanistan is also a country of poets and artists, with a rich history and enormous beauty, and that those fleeing their homeland must leave a great deal behind them.”

It’s an honor for one of my books t o be included in this week’s prescription: “The politics of Western charity and intervention in war-ravaged Afghanistan is the backdrop for Allure of Deceit by Susan Froetschel, in which suspicions of fraud and murder follow the mysterious disappearance of a group of aid workers.”

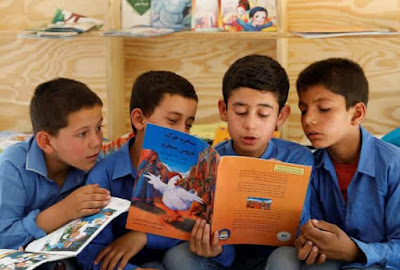

Fear of Beauty, also set in Afghanistan, explored one woman's desperate quest to learn to read. Banned from classrooms, Afghan women had high rates of illiteracy under the previous Taliban rule, which ended with the US-led invasion in late 2001. Since 2016, the literacy rate increased by more than 40 percent, according to UNESCO in a March 2020 report. Still, the literacy rate is 55 percent for men and about 30 percent for women. Reading is the key to new ideas and success, and Afghanistan's readers will resist bullying, authoritarian efforts to dismiss this essential skill.

Books both inspire and record individual dreams, and offer a reminder about how the Taliban will struggle to convince Afghanistan’s 38 million people that reading and education are worthless endeavors.

Photo courtesy of Mohammad Ismail/Reuters and the Guardian.