A child can develop resilience despite domestic violence, neglect and abandonment, poverty and inequality.

In Hang the Moon by Jeannette Walls, Sallie Kincaid is born into a comfortable life in a small, early 20th century Virginia town that is run by her father, known as the Duke, and his sheriff brother-in-law. Soon after her mother dies, the Duke marries a woman who resents Sallie, especially after she has a son who prefers music and education to fishing, hunting, risk-taking and rough-housing.

Tough and matter-of-fact, never bitter, Sallie adores her father and accepts that he wants a strong son to resume control of the family business – a general store that organizes county moonshine sales. After the death of her mother, the Duke's second wife, all Sallie wants is to be part of a tight family. So she respects and gets along with her half-brother, Eddie. She follows her father’s orders to mentor Eddie on toughness, and the two have a wagon accident that nearly kills him. Her father sends Sallie away to live with her mother’s sister, providing minimal support. The child assumes the move is temporary, helping her aunt scrub wash to get by.

Education is an afterthought in the poor community, though a teacher takes a liking to the intelligent girl and relies on her to help with younger students and offering advice that Sallie remembers years later: “teachers don’t know everything, but as long as they stay a step ahead of the students, the students think they do.”

The father sends for Sallie a decade later after the stepmother’s death. Teenaged Sallie is resourceful and loyal, but the father envisions one path for girls, and that is marriage. He expects her to tutor the brother, but Eddie knows far more than she does. She takes advantage of his lessons, but also worries about his values, once asking, “If you’re the smartest person in the room, is it always smart to let everyone know it?” The boy replies, “Absolutely. Nothing is more important than the truth.”

The father marries a third time. Eddie adores the new stepmother and a baseball player friend, and Sallie longs for a “paycheck job,” one where she showed up, worked the hours, and collected a paycheck, allowing her to send money to her struggling aunt. Sallie convinces her father to let the stepmother tutor the brother and make Sallie wheelman – collecting payments from the many land tenants.

As an adult, Sallie learns her father kept many secrets. A black tenant is another half-brother. Her aunt resorted to prostitution after losing the wash business and is mother of half-sister/cousin, a long-time servant. Her father shot her mother after a domestic dispute.

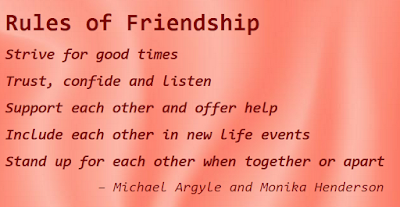

After the Duke’s death, the stepmother quickly remarries the baseball player and agrees that Sallie invite the maternal aunt, a “fallen woman,” into the family home. Eddie and the Duke’s sister protest, and Sadie argues for forgiveness. “People who’ve never gone without find it easy to pass judgment on those who’ve struggled.”

The Duke’s sister and her sheriff husband take control of the business, battling with the stepmother, regarded as an outsider, for guardianship over Eddie. The aunt makes the stepmother’s life unbearable, prompting the woman to flee and Eddie to commit suicide.

Next, an older half-sister and preacher husband take control of the family business, insisting on enforcing Prohibition rules and hiring a ruthless security officer to end moonshine production. Profits plummet and tenants become desperate, testing Sallie’s conscience as wheelman. “It’s when the boss asks you to do something you know to be wrong and you do it anyways. That sort of work whittles away at the soul.”

The sister dies of cancer and Sallie takes control of a failing enterprise, remembering old lessons as she struggles to learn who to trust. She recalls trying to save up for a gun when leaving with her impoverished aunt and a schoolmate offering to let her help his family harvest and sell chestnuts for six cents a basket. “The frost had knocked the nuts out of the trees and the ground was thick with them. Mr. Webb told us we had to make haste, seeing as how bear, deer, boar, and people would all be fighting over these chestnuts and in a couple of days they’d be gone.“ She needs thirty-four large baskets to buy the gun, but comes up a bit short.

Sallie visits the family to collect her share, fulling expecting them to avoid payment. The quiet, stern man advises that the price of chestnuts was not what he had expected, with a blight killing off trees to the north and chestnuts in short supply. The shortage means chestnut prices went up, and he pays her seven cents per basket. “Some folks say they hate to be proved wrong, but I was never happier to be mistaken.”

Based on such experiences – at times, the novel reads as though a series of short stories – Sallie develops her own moral code, running the illegal business but discouraging lies, corruption and long-time disputes. She is quick to forgive and move on, and that policy applies to the paternal aunt who long made life difficult for Sallie, her mother and her aunt. Sallie leads the family and tenants on producing and running moonshine into nearby Roanoke. “Outlaw. Rumrunner. Bootlegger. Blockader. I don’t for one second forget that what we are doing is illegal, but legal and illegal and right and wrong don’t always line up. Ask a former slave.” She adds: “Sometimes the so-called law is nothing but the haves telling the have-nots to stay in their place.”

She maintains the operation doesn’t involve stealing or coercion. “Just helping out the people of Claiborne County who through no fault of their own are in an awful bind. Obey the law and starve. Or break the law and eat. Not a lot to ponder there.”

For Sallie, family is sacred, and she realizes her father “whose approval I so craved” did not feel the same. The Duke “loved being loved, but he never truly loved anyone back. He took what he wanted from people, then once he got it, cast them aside.”

The historical novel is bittersweet, optimistic and certainly idealistic about bootlegging and a woman running a business in the 1920s. Sallie succeeds by embracing all members of her family and community, wayward in so many ways, as long as they get along and work to love and protect the whole.