Friday, April 8

Lies and details

Thursday, March 3

Lessons

In this unconventional American Western, How Much of These Hills Is Gold, a Chinese-American family pursues a hardscrabble life, prospecting for gold and working other mines with two goals. Ba, the father, wants to buy his own plot of land, and the mother longs to return to China. Set in the mid-1800s, the family confronts slurs and discrimination while the two daughters – Lucy and Sam, ages 12 and 11 – endure a mixture of abuse and tough love at home. It's easy to imagine members of this family questioning, “can you love a person and hate them all at once?”

Both girls are smart, adapting to new settings, as the family moves in search of work and a sense of home. Lucy openly yearns for a formal education, much like Sofi in Fear of Beauty, but poverty, discrimination and her father’s general mistrust prevent her from consistently attending classes. Sam, with another set of desires, nurtures the ability to keep secrets.

The story begins after their father’s death in 1862 and the girls’ flight from a mining town, and the book leaps from past to present and back, with the story of the journey, separation, reunion and a heap of painful memories: their father’s upbringing and parents’ meeting, the death of a baby brother, their mother’s disappearance, the quest for work, comradery, and respect.

The parents make no secret of their longtime preference for a son, and Sam takes to cutting her hair, dressing in boy’s clothes and accompanying her father to the mines for work, all the while regarding her body as “a temporary inconvenience.” Lucy struggles to understand Sam who wants to be a cowboy, an adventurer, an outlaw and concludes that her sister is “Young enough to think desire alone shapes the world.”

Lucy gathers intently observes and listens to others – including her parents and strives to please anyone who might teach her. She discovers lessons in agreement, politeness, trickery, shame and “imagining herself better” along with the disappointing stream of “Lessons in how other people live” and “Lessons in wanting what she can’t have.”

Often, when trying to please others, when not moving through the wilderness, she loses her identity and values.

As a child, Lucy resists the notion the family might return to China, insisting she does not want to live with other Chinese, blurting out a common ethnic slur herself. Her father, in one of his gentler moods, whispers the Chinese word for Chinese people, and the two sisters “let the name for themselves drop down the cracks in their sleep, with a child’s trust that there is always more the next day: more love, more words, more time, more places to go….”

One of the most haunting parts of the book is the father’s background story, relayed after his death by the wind sweeping over the land. The orphan, raised by Natives, former slaves and others ostracized by society did not grow up with people who looked like him. “But that’s not an excuse, and don’t you use it," he admonishes Lucy. "If I had a ba, then he was the sun that warmed me most days and beat me sweaty-sore on others; if I had a ma, then she was the grass that held me when I lay down and slept. I grew up in these hills and they raised me….”

The father cherished wildness, and Lucy wondered if that was the “sense that they might disappear into the land – a claiming of their bodies like invisibility, or forgiveness?”

Other lessons are brutal and erratic as the father teaches the mother English, the mother teaches the father Chinese, and both parents guide their girls on how to be tough and endure adversity. The isolated, beautiful, and crafty mother urges her daughter to find choices: “’[B]eauty’s the kind of weapon that doesn’t last so long as others. If you choose to use it – mei cuo, there’s no shame. But you’re lucky. You have this, too.’ She raps Lucy’s head.”

The alcoholic father’s angry cruelty forges a connection between two young women with many differences. Lucy also absorbs lessons on injustice, loyalty, gratitude as well as the land's harsh beauty. “I looked for a fortune and thought it slipped between my fingers, but it occurs to me I did make something of this land after all – I made you and Sam…. I taught you to be strong. I taught you to be hard. I taught you to survive…. I only wish I’d stayed and taught you more. You’ll only have to make do with bits, as you have all your life.”

Regardless of hate, love and other emotions in between, the father repeatedly drills the girls on one key lesson. Family comes first. Ting wo. Of course, such fierce loyalty means freeing other family members freedom to go their own way.

Tuesday, March 1

Neighbors at war

Russia's president, rattled by NATO and nostalgic for the Soviet Union and Cold War, invaded Ukraine after the latter's leadership rejected a pledge to not join NATO. Russia has also threatened others. “President Vladimir Putin has demanded NATO withdraw all outside forces from the region and commit to Sweden and Finland never being allowed to join,” reports Edward Lucas for Foreign Policy.

Putin's use of brute force in Ukraine provides new incentive for Finland, Sweden and Ukraine to pursue NATO membership.

NATO leaders met on February 25, calling on Russia to stop the “senseless war” – and to “immediately cease its assault, withdraw all its forces from Ukraine, and turn back to the path of dialogue and turn away from aggression.”

NATO’s 30 allies contribute to the budget on an agreed cost-share formula based on gross national income – “This is the principle of common funding, and demonstrates burden-sharing in action.”

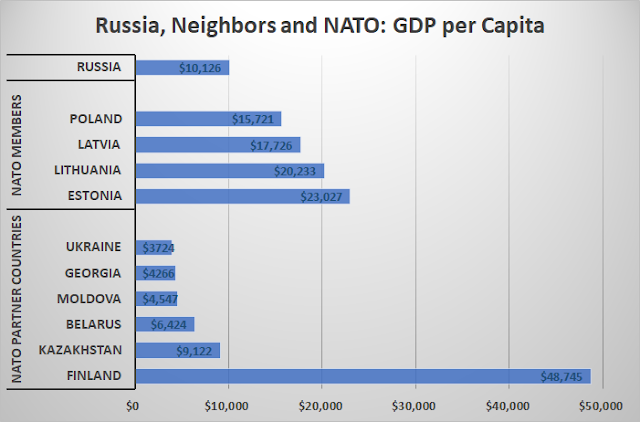

The US State Department describes US cooperation with NATO’s three Baltic State members – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The countries bordering Russia have shouldered the security responsibility, reports Lucas. “The Baltic states and Poland play their part too: Their defense budgets exceed the minimum 2 percent of GDP mandated by NATO. These funds are spent wisely, including on modern weaponry that could at least slow, and thus help deter, a Russian attack.”

NATO is supporting Ukraine against Russia’s aggression: “Thousands of anti-tank weapons, hundreds of air-defence missiles and thousands of small arms and ammunition stocks are being sent to Ukraine. Allies are also providing millions of euros worth of financial assistance and humanitarian aid, including medical supplies to help Ukrainian forces.”

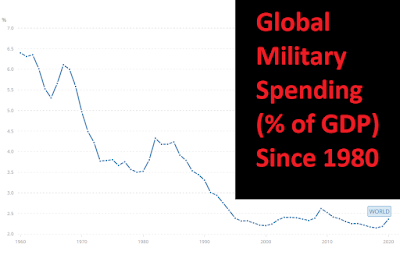

Global military spending as a percentage of GDP has been in decline since the end of the Cold War, but Russia's current leadership is intent on reversing that trend.

So far, the Ukraine military, aided by citizens under siege are slowing the Russian invasion. NATO members – along with many other countries – are imposing harsh economic sanctions on Russia that could plunge the country into a depression as long as President Vladimr Putin is in charge.

Data on military spending for Russia and selected neighbors from the World Bank.

Monday, February 28

Neighbors

Data on GDP per capita is from the World Bank.

Thursday, February 17

Inequality

The Glass Kingdom, creepy and suspenseful from the start transforms to simple horror by the end, masterfully detailing the resentments that emerge over inequality and the ways that individuals justify stealing from others: “It was a war between herself and the moneyed classes, and in that war all ruses were legitimate, all feints justified,” concludes Sarah soon after creating and selling a set of forgeries, presented as correspondence from her most recent employer, a famous author. Committing a crime eliminates social protections, and when encountering trouble later, Sarah cannot turn to authorities: “It was too late, in any case, to become an upright citizen and call the police.”

A reader

must suspend belief about the plot and numerous character decisions. Why would

the author retain her own handwritten letters to celebrities like Angela Davis

or Diana Vreeland? Why would collectors sell them to the author and not to the other

collectors seeking them and paying a premium price? Wouldn’t the collectors have

direct dealings? And Sarah’s transport of a couple hundred thousand by air, crossing

international borders, would surely be much riskier with more challenges than

described.

Then again,

people are odd, sometimes extraordinarily lucky or unlucky as the case may be. And

loneliness – so familiar during the Covid pandemic – compounds the poor

decision-making displayed throughout the novel: “The burden of that solitude

had begun to crush her hour by hour.” Sarah fails to recognize the assuming manipulations

of a new friend Mali who requires assistance in covering up another crime, not posing questions or objections after Mali suggests: “Let’s do it my way, OK?

I’m sorry to get you involved, though,” quickly adding, “We’d both like that, no?” Finally, why would a young woman not quickly abandon a hotel losing

guests, let alone a city with increasing civil unrest?

The dark and

moody novel powerfully demonstrates how inequality makes trust or mutual respect

impossible. Characters are divided not only by wealth and skill, but ethnicity

and religion. A hotel maid concludes that the farangs, referring to foreigners, are “animals in their hearts, untouched by the grace

of Lord Buddha” – and they exist in a “prison of their own making, and she

entered that prison only to make a living. For in the end there was no other

reason to enter it at all.”

The book conveys that life is unfair at every level. Highly visible, cruel inequality ensures that sinister unfairness and corruption never end.

Wednesday, February 16

Memories of love

The Parted Earth is a family saga that begins with the 1947 Partition of India. A teenager, Deepa, observing and worrying how New Delhi and neighborly relations can change violently in a short period of time, recalls a comment from her mother: “People are inherently good… they’re just not inherently good all of the time.” The comment ominously foreshadows the ethnic hatred and violence of the Partition, turning neighbors against neighbors and even some parents against children, as noted by Stanford’s Partition Archive:

“Up to two million people lost their lives in the most horrific of manners. The darkened landscape bore silent witness to trains laden with the dead, decapitated bodies, limbs strewn along the sides of roads, and wanton rape and pillaging. There was nothing that could have prepared the approximately 14 million refugees for this nightmare. The 1947 Partition of the Indian subcontinent into the independent nations of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan was accompanied by one of the largest mass migrations in human history and violence on a scale that had seldom been seen before.”

The book begins sweetly, taking on the tone of a young adult novel while describing the happy life of Deepa, the only child of two progressive physicians. But violence and chaos mark the summer of 1947 with India on “the verge of a war with itself.” The brutality and separations haunt survivors long afterwards, lingering for generations. For those who witnessed the atrocities, “Distance and time were inconsequential.” Collective grief ensures loneliness, trust is fragile, and parents struggle to explain events to their children. Withholding information about a child’s father, conceived during the chaos, is cruel. Learning horrific truths about a parent’s role in atrocities is perhaps even worse.

Deepa bears a son, Vijay, who searches for the father he never met and answers about his mother’s resentment. A search in India and Pakistan separates him from his daughter, Shanti, who is 10 and raised in the United States.

Every character, during the days of Partition and long afterward, is left feeling as if he or she could have done more – displayed more grace, more compassion, more patience.

Unlikely friendships that cross generations and cultures bring comfort, new perspectives and even rescue. For Vijay, it’s Miss Trudy – his mother’s friend who cares for him and treats him as her own. His mother was stern, ensuring completion of homework, assigning extra math problems to do and books to read, providing shelter and food. Yet “Miss Trudy taught him how to make dough rise for bread, how to sew on a button, how to draw a dragon, kick a football…. She tended to his skinned knees, comforted him when his classmates called him a half-caste bastard. Miss Trudy let him be weak, so that when his mother picked him up in the evenings, he could pretend to be strong.”

Deepa is furious after Miss Trudy poses the boy's questions about Vijay’s father. More than anything, Deepa feels “betrayal… sudden understanding about the special closeness her son shared with his babysitter, instead of his own mother.”

Years later, Shanti, wonders why Vijay, her father, was so distant, spending so much time in India. In her forties, she forms and embraces a friendship with an elderly widow next door, whose husband committed suicide, and the two women share details from their pasts.

Sharing stories and close listening pays dividends as Shanti finds the widow’s husband on a website that documents Partition experiences, and the widow locates the sister of Vijay’s father, Shanti’s grandfather, in Pakistan.

Planning for Partition and the aftermath with mass migration, surging resentment and violence, spanned a few months, but the rebirth, renewal, and forgiveness required years.

Shanti spent only a few days at a time with her father, but is grateful to have known his love. “She didn’t have it for long enough. But now, in her forties, she felt it stronger than ever. She would hold on tight to it and never let it go.” Love, however brief, is embedded in memories, providing strength to trust and care for others even while handling loss.

Saturday, January 29

The purpose of children

Scarlett Chen, impregnated by her employer, is sent to a secret home in California, with the goal of obtaining US citizenship for the infant. The employer, already married with three grown children, is possessive, "acting as if he had a right to her every thought, to her every move." Perfume Bay is more prison than resort, and Scarlett is furious when the home's manager, Mama Fang, hands over payment and expects her to give up any claim to the child. Mama Fang had hardened herself to the cruelties of such an unscrupulous business, vowing to watch out only for herself. “She did not know then that this vow would harden her. If you only looked out for cheats and con artists, you only found cheats and con artists. You became one yourself.”

Scarlett refuses to comply. Raised by an angry, controlling woman whos enforced strict one-child limits in their poor village, she resents inequality, being told what to do. And so Scarlett flees Perfume Bay. "America called to her: the land of cars, of fast highways that opened up the country that she'd always wanted to explore, the country where she could make a life for her daughter." She soon discovers that the corruption and inequality of factory work in China are not so different from the tough scrabble in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Compounding her stress – a soon-to-expire tourist visa means that she must dodge immigration authorities as well as the detectives dispatched by her lover and his friend to hunt her down.

Vanessa Hua analyzes the role of children and families, and the struggle for immigrants to the US, where “even the most prosperous had to endure snubs, slurs, and worse.” Families become insular and children become the means for pursuing a better life. “For the poor, children doubled as their only retirement fund. For the well-off, their children were still a kind of currency, in the rivalry among one’s friends and colleagues, and in the lifetime tally of success.”

Such goals become futile as parents approach end of life, and one character observes: “The prospect of death coming closer made you consider your life, what you wanted in what remained.”

Raising a child in harsh conditions, the need to sacrifice, Scarlett gains a new perspective on life and gradually comes to understand her mother’s tough ways. Valuing and using her ingenuity and setting firm priorities, Scarlett becomes more intent on giving to her immediate family and friends rather than taking.