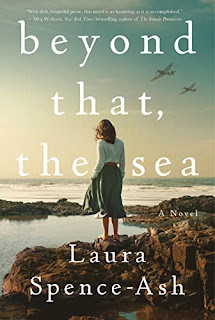

In Beyond That, The Sea by Laura Spence-Ash, Londoners Reg and Millie Thompson disagree but ultimately decide to protect their daughter at the start of WWII, sending Beatrix to live with a family they do not know. The mother is less sure about this plan, sending the teen to the United States. and the couple frequently argues. Beatrix feels a distance: “I stopped being a child on the day war was declared,” she thinks. “And you both disappeared even as you stayed by my side.”

The novel follows the connections between two families - the choices, mistakes, dreams and regrets. From all appearances, the Gregory family enjoys a comfortable life in the Boston suburbs with long summers on their own island in Maine, a home Nancy inherited from her wealthy parents. The father teaches at a private school, and the family lives on campus. Nancy always longed for a daughter and embraces Bea as her own, buying her new clothes, praising her schoolwork and anticipating every concern. There is no jealousy, and Bea gets along well with the two Gregory sons, William who is a year older and Gerald a year younger. This family relishes the guest, truly caring about her opinions, and the two boys compete for her attention.

Maine in summer is one of the world’s gentle places with routines as steady as the waves beating against the shore. As war rages, the three children feel guilty about their good fortune, and each contributes to the war effort in small ways. Bea, the best student of all, understands her family cannot afford college. She especially feels guilty about her parents’ proximity to the war and also not missing her parents more as she falls in love with a new family and way of life that allows freedom and access to the natural world. Her guilt intensifies after her father dies in 1943, and the two boys respond in contrasting ways. Gerald asks what she thinks happens after death: “Do you believe in that stuff from church, about heaven and hell and all that? Or is it just over. Is your dad just gone?” At another point, William overhears her talking with her father in a local cemetery and, blunt like his father, retorts, “He’s not there…. He’s dead.” William, blunt and opinionated like the father with whom he clashes, long regrets his impulse to hurt.

With war underway, the teenagers are uncertain about a benevolent God and struggle to accept religious teachings. Gerald confides he wants to believe and imagine Bea reuniting with her father. Likewise, he confides that all he wants in life is to return to the island summer after summer and be buried there. Bea understands. “To think that she could have lived her whole life and never seen this island. This place that feels like home.”

The war ends before the males are called to serve. Bea returns to London where she takes up work as a child care provider, remaining upset that her mother remarried before her return and restless about the limitations for her in Britain. She worries about William squandering potential as his letters switch from excitement over classes to parties and bars. After college, while William is in France, his father dies – severe wound for the entire Gregory family. Returning for the funeral, William takes a detour to London to visit Bea and admits that he has a pregnant finance. The two revive their romance, a feeble attempt to revive memories of idyllic childhood, and Bea’s mother arrives home early from a trip, interrupting the couple’s final hours together. During the brief encounter, Bea recognizes how neither fully understands the other’s goals or state of mind, and she muses “how difficult it is to know someone’s past.” And perhaps William could not understand because “she had let her past slip away. She had instead, become part of his world, of the Gregory world.”

Bea sees only a few hints of the William she once knew, admitting that she is at odds, too. “My favorite place? Maine. My favorite food? Your mother’s muffins. And yet here I am. This is my home…. I belong here and yet I’m in limbo, really, caught between two worlds. I can’t seem to find where I fit.”

By his mid-thirties, Will finds himself stuck in a deadening job and a loveless marriage. He drinks to excess, wandering around beaches and dance clubs, watching others and wanting to warn them: “Enjoy this, he wanted to say. Try to stay in the moment. He wished he could be one of them, to still be in the place where everything seemed possible.” William, having lost all purpose, knows that an idyllic childhood does not guarantee happiness.

Bea senses William’s darkness from correspondence. “He never said anything, specifically, but under and between the words, she could feel his uneasiness. Not unhappiness, per se, but a feeling that nothing was quite aligned. That the life he’d wanted, the one he’d expected, had failed to appear. It was as though that fire that had once been in his belly – his desire to be in the world – had somehow been extinguished. She wondered whether he’d ever been truly happy.”

William and the rest of the family remain a constant puzzle for Bea. “I just wanted – we all just wanted – you to be happy,” she says out loud, talking up to the blue sky. Why is that difficult for so many people to achieve?”

The novel’s chapters are brief – each told from the point of view of one of the parents, children or spouses but most often Bea and William – most ending with characters reaching new insight. Bea visits New York again seventeen years later, yet avoids reaching out to the Gregorys. That following Christmas, she sends gifts to the family and the clerk asks if she has family the States. “No, she starts to say and then changes her mind. Yes, she says, Yes, I do.”

Millie, long jealous of Bea’s attachment to the Gregorys, accompanied her daughter to New York and gradually begins to understand the attraction. “There was something being there in America, that made Nancy come alive to Millie in a way she never had before. Her openness was a classic American trait, one that Millie had never quite believed. And yet here they were, all these Americans, being loud and friendly and willing to talk to you about almost anything.” Millie admits to admiring Nancy and admits that, had the tables been turned with war in the States, she could not have embraced a stranger’s child as her own.

Millie and Bea slowly forgive each other with weekly walks in the park. “There’s something to be said for talking while walking. You don’t have to look at the person. You can keep your eyes on the path, on your shoes, on the landscape. And somehow that means that more gets said.”

After William’s death, Bea attends his funeral and reconnects with Gerald. Nancy observes them together and thinks about how strange it must be for them without William. “Those summers in Maine, those few sweet summers when the three of them were thick as thieves. Those days that passed by far too quickly and that she can only remember snippets of now. The three of them, racing out to the dock, King following behind. Picking blueberries in the hills. Camping out in the woods. Late at night, the world quiet around them, the lights from the house reflecting in the dark sea. Oh, why can’t time be stopped in those moments. Why is it so hard to understand how fleeting it all is?” Desperate to connect with the past, she feels the “need to scramble back in time, to pull up old memories, to regret words, to re-create moments.”

After finding love with a third husband, Millie feels secure enough to release Bea, and the newlyweds encourage Bea to attend William’s funeral. Bea confides that the Quincy house is “the place that feels like my home” and Gerald asks her to stay, to truly make it her home. Holding his hand, Bea responds, “Let’s take a walk, she says. Let’s take a walk.”

William’s untimely death along with an incomplete tale from Bea – some might call it a lie, others would argue that the entire past need not be exposed – end the ruthless competition between two brothers. Gerald and Bea marry and repurchase the island home in Maine, presiding over another stretch of perfect summers with Nancy, their child and William’s children. It may be distressing to ponder whether we are each at our purest, our finest, during childhood. Still, this exquisite book on family relations has a happy ending, as Bea lovingly, naturally resumes the matriarch role for the next generation of Gregorys.