Friendships can move from lightness to darkness with age, experiences and the blunt truth, as suggested by a novel of two girls growing up in Karachi – Best of Friends by Kamila Shamsie.

The teens relish their friendship, “the certainty that whatever happened in the world you would always have this one person, this North Star, this rock, this alter ego who knew your every flaw down to your atoms and who still, despite it all, chose to stand with you and by you through everything that the world had yet to throw at you, every heartache, every disappointment, every moment of darkness.”

One family is adept at navigating a corrupt culture and the other yearns for freedom - and years later, a friend can become a source of darkness.

Maryam is wealthy and assertive, confident she will bypass her father to inherit her grandfather’s leather company, a rough business with workers and competitors brutalized into compliance. Zahra and her family are less wealthy though content and intellectual. Zahra grows up respecting her parents’ integrity. Her father hosts a television show about cricket, and much like “journalist friends who had spent years navigating a path between conscience and consequence,” resists a demand from the Zia administration’ to credit the dictator for one victor. Dictatorship and everyday violence “had shrunk all their lives into private spaces,” she muses. Zia dies soon afterward, and the girls celebrate the new government led by Benazir Bhutto. Still, a new government does not eliminate corruption and controls from Pakistan.

The wealthy are accustomed to using and scapegoating others. Maryam demands that her driver let her operate the vehicle without a license. The grandfather warns Maryam that he wants her to be fearless, but “not like every other soft, silly girl,” “spoiled and reckless.” The grandfather fires the driver and “She recognized, but couldn’t change, the awfulness of being less upset about Abu Bakr’s fate than she was by the tone of disgust in her grandfather’s voice when he told her she had ceased to be exceptional.”

Not long afterward, the two girls attend a party and Zahra jumps into a car with older boys, including one admired by Maryam. Maryam follows, and a few hours of terror ensue until Maryam commands the boys take them home. The school expels Maryam's friend, and neither girl corrects the parents or schoolmistress about Zahra’s role as instigator.

Once again, the grandfather expresses deep disappointment, asking what kind of person Maryam is. She responds: “The kind of person you’ve taught me to be.” The grandfather dismisses the family. “I thought I could make you want you need to be. But you’re just a girl, aren’t you? You’ll always be a girl. And there’ll always be Jimmys out there who’ll see through everything else and know that. Perhaps I should be grateful to him for making that so clear.” Maryam insists that she has more to learn from her grandfather and he retorts: “You’re learning all the wrong things. Self-absorbed and willful. No moral center. You’ll never be who I need you to be.” Maryam’s parents send her to boarding school in England, and the two women reconnect, attending college in London and launching successful careers.

In forming friendships, children overlook class, race, and sometimes even values. Neither woman remembers what triggered their first connection. “The exact origins of their friendship were lost in a past that stretched back beyond memory.” Shared interests, admiration, convenience connect children. Adults connect via values.

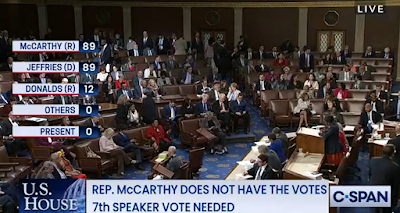

With age comes assumptions and even secrets and lies. “Deep down they both knew that no one had the kind of friendship when they were forty that the two of them had at fourteen.” The two women have contrasting careers and personal lives. Maryam is a venture capitalist and founder of founder of a tech image-sharing firm that involves facial recognition and privacy concerns. Zahra is a civil rights activist who worries about Britain’s complacency over democracy: “things that would set off alarm bells in countries with histories of authoritarian rule are allowed to slide by here.” She is capable of whipping up protests but worries about modern motivation. “The tens of thousands, maybe more, who showed up at rallies had less and less the air of people determined to bend the arc of history toward justice these days, and more and more that of those in need of a support group.” Zahra has little patience with despair, especially after growing up with conflict, viewing the feeling as a luxury and self-indulgence.

Zahra fights for rights of strangers, yet her personal life is mostly limited to Maryam and her family. Maryam, left-wing when profitable, fiercely protects those close to her and has little sympathy for strangers. “The world was exactly as her grandfather had always taught her it was,” Maryam reflects. “Terrible and brutal, unforgiving. But she also knew the truth that followed on from that, which he had failed to understand: Hold close the ones you love, protect them. There is no other source of light.”

The two never fully talk about the terrifying night in Karachi, and too many assumptions are made, too many accusations withheld. “The problem with childhood friendship was that you could sometimes fail to see the adult in front of you because you had such a fixed idea of the teenager she once was, and other times you were unable to see the teenager still alive and kicking within the adult.” Zahra comes to realize that “perhaps friendships weren’t all about what you said to each other but also about what you didn’t say.”

The friendship reaches a breaking point after Maryam uses her software, takes revenge on Jimmy years later, prompting his expulsion from Britain, and Zahra feels compelled to resign from her prestigious position. An ugly rupture might have been avoided had the two women talked more about that night.

Zahra may need the friendship more. While appreciating her home as a quiet refuge, “she found herself imagining a day – not soon, but eventually – when loneliness would stalk indoors and refuse to be evicted.”

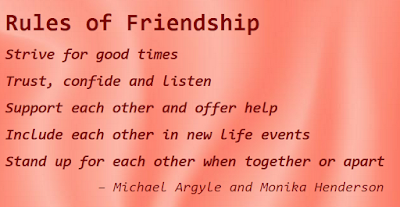

A lifelong friend – a person who understands your background and culture, your dreams and fears and history – is a treasure. Yet full adult friendships require a secure foundation of values. Friends need not always agree with friends, suggests Nir Eyal in Psychology Today “Values are not synonymous with viewpoints. You can maintain friendships with people who don’t share your politics, for instance—as long as you both share the values of seeking understanding, keeping an open mind, and arguing constructively.”

Though friendships are essential, many older people struggle starting new ones. Cultivate and invest in relationships, including periodic assessments to avoid treacherous patterns. Friendships fade, suggests Jennifer Senior in a beautiful essay for The Atlantic, concluding that it's actually unusual for such relationships to last.

Friends shape how we live and even think, and deliberate choices are in order.

Image courtesy of "The Rules of Friendship" by Michael Argyle and Monica Henderson.