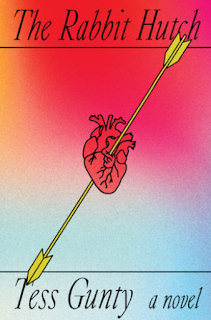

Most readers quickly and rightly reject novels that detail abuse of animals, children or other vulnerable populations. Reading about systemic poverty and lack of opportunity – the slow neglect and breakdown of human spirit – should be equally disturbing. The Rabbit Hutch alludes to first while detailing the humiliations and weariness associated with the second.

The debut novel by Tess Gunty explores how individuals slide into disturbing behaviors, influenced by surroundings, circumstances and other people. The setting is a dilapidated apartment building known as the Rabbit Hutch in Vacca Vale, a dying Indiana industrial town. Most occupants resent and avoid their neighbors. These include a quiet middle-aged woman who moderates comments for online obituaries and four young adults recently aged out of the foster-care system.

The characters are flawed, insecure in this desolate environment. A visitor from Hollywood, the depressed son of a child movie star, suggests that other people are "dangerous because they are contagions. They infect you with or without your consent; they lure you onto paths you wouldn't have chosen.... if you collide with someone, you must be prepared to reside inside their psychology indefinitely, and this is the burden of a lifetime." These characters, struggling to communicate and launch meaningful relationships, do collide rather than connect.

The discomfort over an inability to find companionship is not limited to dying communities, and the visitor from Hollywood concedes that his own conversations with others are a mess as "he doesn't know how to have clean ones anymore."

While in Vacca Vale, he wanders into a church and agrees after a priest asks if he is there for a confession. After describing his fears and worst behaviors, the man questions the priest’s assessment. The priest admits to weariness and advises the confession might be his last. Unleashing regret, the man mourns “rot at the center of the Catholic Church,” Rather than effect change, the priest felt infected. “Abuse should be condemned. Birth control should be encouraged…. These are easy things, obvious things, unavoidably right and good, and yet I’ve come to believe that they’re never going to happen within this decaying institution. I’m sick of following orders, meekly playing the game, waiting for the rules to change themselves.”

His complaints target one institution, yet capture the dilemma of anyone trapped within systems, playing by questionable rules while ignoring massive, obvious problems. The priest counsels the visitor that no person can be all good or all bad. “You’re just a series of messy, contradicting behaviors, like everyone else. Those behaviors can become patterns, or instincts, and some are better than others. But as long as you’re alive, the jury’s out.”

Progress depends on breaking old patterns, avoiding old mistakes.

|

| St. Blandine |

The apartment is the first for the foster children, three young men and a woman, Tiffany. She is intelligent, well-read, but she drops out of high school after a misguided affair. Despite or maybe because of her own history of hurt and neglect, she continues to study and learn, touting a library copy of

She-Mystics: An Anthology and adopting the name of

Blandine, a slave girl martyred for her Christian beliefs in the 2nd century. The teenager stands out as odd, fascinated less by religion and more by ethics, philosophy, and ancient saints who practiced self-abuse to achieve immortality and godliness.

With a few exceptions, Blandine is wary of new relationships – "My whole life has educated me against investments whose rewards depend on the benevolence of others."

And so she regards

Hildegard, a mystic from the 12th century, as her only true friend, relying on quotes for guidance: “Even in a world that’s being shipwrecked, remain brave and strong” and “Humanity, take a good look at yourself. Inside, you have heaven and earth, and all of creation. You are a world – everything is hidden in you.”

|

| St. Hildegard von Bingen |

Blandine ponders how the mystics, despite their gender and solitude, left their mark on history and human thought. And while she does not believe in God and regards the mystics as selfish and individualistic, she wonders how a modern mystic might challenge climate change, systemic injustice, the “plundering growth imperative,” and other obvious challenges in Vacca Vale.

Ambition mixes with fear, and Blandine admits to often being “attacked by an awareness of how impossible it is to learn and accomplish all that she needs to learn and accomplish before she dies.” She denies herself a high school scholarship, the chance to attend college, appropriate roommates all while searching for virtue in a community seeping with inequality, corruption, insecurity and depression. Reflecting on her own life, she concedes that "It all looks so - so grotesque." She longs to transform her community but lacks tools to intercede.

Another neighbor – Joan, the editor of online obituaries – is fearful and lonely, witnessing the pain of Vacca Vale on a more personal scale. One day while walking, she observing the impulsive ease of strangers demonstrating care for a person who collapses on the street. She understands that “human tenderness was not to be mocked. It was the last real thing.”

The disjointed plot is relayed with exquisite sentences. The theme is strong – people can transform, breaking habits and moving the many obstacles they have placed in their own way by practicing kindness. A brief and awkward encounter between Joan and Blandine in the book’s earliest pages isn't the last. The two women discover a shred of connection – thank to persistence, hope, empathy – hundreds of pages later.